Bowl, Jingdezhen, China, ca. 1572–1620. Slip-decorated porcelain. D. of footring 2". (Courtesy, Jamestown Rediscovery Foundation; photo, Robert Hunter.) This fragmentary example was recovered from disturbed archaeological deposits at James Fort.

Bowl, Jingdezhen, China, ca. 1572–1620. Slip-decorated porcelain. H. 2 3/8". (Private collection; photos, Robert Hunter.) This bowl was recovered as an archaeological find in Bantam, Java, and restored.

The archaic mark on the top bowl, recovered in Bantam (and illustrated in fig. 2) is the same as that on the bottom bowl, recovered from Jamestown (and illustrated in fig. 1). (Courtesy, Jamestown Rediscovery Foundation; photo, Robert Hunter.)

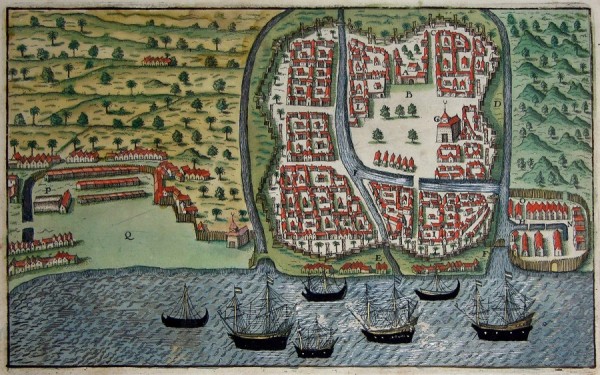

Johann Theodor de Bry (1560–1623) and Johann Israel de Bry (1565–1609), Part III, Bird’s-eye View of the City of Bantam. From Orientalische Indien [Little Voyages], Dritter Theil indiae orientalis (Frankfurt, 1599). Colored engraving on paper. 9 7/8 x 6 1/8" (image). (Wikimedia Commons.)

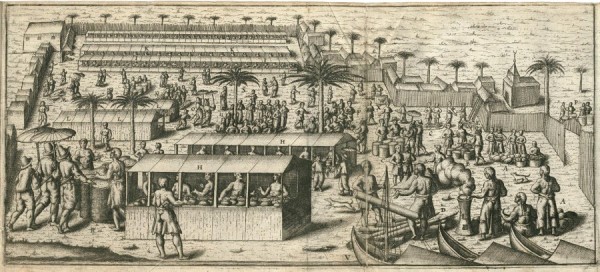

Unidentified engraver, View of Bantam Market, Cornelis Claesz (publisher), Amsterdam, ca. 1598. Engraving on paper. 7 3/4 x 21 1/2". (Koninklijke Bibliotheek, The Hague.)

Unidentified artist, Captain Robert Adams, England, 1626. Oil on canvas. 43 1/4 x 35 1/2". (Courtesy, Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Gift of Hugh W. Long, 48.4.1.)

Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger (ca. 1561/62–1636), Sir Thomas Dale, ca. 1609–1619. Oil on canvas. 80 1/4 x 45 1/4". (Courtesy, Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Adolph D. and Wilkins C. Williams Fund, 52.8.)

For the 2017 issue of Ceramics in America I wrote about a slip-decorated Chinese porcelain bowl as one of my top-ten favorite ceramics from the archaeological excavations of the Virginia Company Period contexts of Jamestown, Virginia (fig. 1).[1] While it remains an all-time personal favorite, the recent discovery in Bantam, Java, of a parallel vessel truly set my heart aflutter (fig. 2). I had searched high and low for another example of the porcelain bowl that, to this day, is a unique find in colonial America.[2] Now, through this recent discovery, we can consider a possible biography for the Jamestown vessel as it traveled in the early seventeenth century from the place of its creation—Jingdezhen, China—to the isolated English settlement half a world away.

The bowls are decorated on the exterior with a dark blue ground over which is painted in white slip the traditional Chinese motif of dragons in pursuit of the flaming pearl. In Daoism, the dragon is believed to be the keeper of auspicious powers, including wisdom, as symbolized by the pearl. The dragon bodies are further embellished with incised lines for scales and the thick slip creating the creatures’ bodies makes them stand proud of the vessel, creating a wonderful tactile sensation beneath one’s fingers.

Slip-decorated wares with a raised white slip on a contrasting monochromatic ground were produced in both Jingdezhen (Jiangxi province) and Zhangzhou (Fujian province) during the reign of the Wanli Emperor (1572–1620).[3] As I mentioned in my 2017 article, until the base of the Jamestown dragon bowl was recovered by archaeologists, the vessel was thought to be a Zhangzhou product. But the base bears an archaic Chinese mark that has been found only on porcelain manufactured in the private (folk) kilns of Jingdezhen. The base of the Bantam bowl bears the same mark and, like the designs on both bowls, appears to have been painted by the same hand (fig. 3). The underglaze-blue marks read yu tang jia qi (“exquisite vessel from jade hall”).[4] In Daoist literature, jade hall is the legendary beautiful residence of the immortals.[5] In other words, the decorator of the bowls was declaring them of a quality that was worthy of use by the deities.

Bantam, Java and the East India Company

Why would a lovely piece of porcelain made in Jingdezhen end up in Bantam (modern-day Banten)? As a port city and sultanate on the northwest coast of Java in the Indonesian archipelago, Bantam was an important global trading center for maritime Southeast Asia beginning in the sixteenth century (fig. 4). The newly formed English East India Company (EIC) established a trading factory there in 1601 with the goal of breaking the Dutch monopoly on the Asian spice trade. But the Dutch East India Company (VOC) followed suit in 1603 by also establishing a factory in the city. Both took advantage of the Chinese junk commerce coming out of Fujian province and controlled by Chinese merchants residing in Bantam (fig. 5). According to the personal journal of John Jourdain, chief factor for the EIC at Bantam, “three, four, five and six juncks from China” sailed into port every February “bringing divers sorts of commodities.”[6] Initially, “fine and coarse porcelain” was a minor part of the trade that brought an “abundance of raw and woven silk” as well as pepper and other spices.[7] While porcelain circulated in maritime East India and was commonly used in the EIC factories, the small amounts of porcelain imported by the EIC at this time were primarily for diplomatic gifts.[8] It was not until the beginning of the eighteenth century, when the EIC was trading regularly with the Chinese from Canton (modern-day Guangzhou), that porcelain became a principal commodity along with silk textiles and tea. Even so, the company concentrated on inexpensive porcelain vessels and left the more expensive decorative wares and specially commissioned armorial pieces to “the private trade of their servants and ships’ oYcers.”[9]

From the outset, personal dealing in goods such as porcelain that were not considered principal commodities of the EIC was tolerated and considered a perquisite for its employees. The company’s instructions to Henry Middleton, the commander of the EIC’s second voyage in 1604, prohibited private trade in such things as “pepper, cloves, mace, nutmuges, China silke, indigo, ambergreece,” and so forth, but stated that any merchant, master, or mariner could “lade some small proporcion or quantitie of China dishes or light triffles, not exceeding the value of three poundes, or not beareing above the bulcke of a small chest.” Such goods were to be recorded with the ship’s bursar in case the owner died, so that “their freindes may enjoye that which is theirs, according to their wills.”[10]

Until the middle of the seventeenth century, the High Court of Admiralty protected the customary rights of mariners to carry trade goods to supplement their wages. The captains and other shipboard personnel in positions of authority had more opportunities to do so, “but sailors on all commercial routes, of all ranks, participated in trade.”[11] The result of this privilege can be seen in the assemblage of exotic imports recovered during archaeological excavations in 2000 from Limehouse, the vibrant maritime community just to the east of the City of London.[12] The pottery, glass, and other goods from dwellings dating from the sixteenth through the eighteenth century are atypical for contemporaneous residences in the city, and reflect the special access to goods enjoyed by these seafaring

individuals.

This assumed prerogative of seafarers led to problems during Jamestown’s early years despite the efforts of colony leadership. Mariners dropping oV colonists at Jamestown realized the marketability of the region’s resources, particularly the “otter skins, beavers, rokoone furs, bears skins, etc.” for which they participated in a black market trade with the Virginia Indians.[13] One sailor reputedly sold £30 worth of Virginia furs in England at a time when the Jamestown colony had acquired none.[14] To add insult to injury, unscrupulous mariners also pilfered from supplies intended for the colonists and then offered the appropriated goods back to the Jamestown settlers at exorbitant rates. According to colonist William Strachey, the sailors expected advance payments of “four or five for one” on the colonists’ bills of exchange for a “dust of corn” or “a pint of beer” even though those victuals had been “purloined and stol’n.”[15] Described by Strachey as an “East Indian increase,” the rate of four to one was evidently the customary arrangement for the commerce of mariners sailing for the EIC.

The Jamestown Connection

In the early seventeenth century, mariners from the Limehouse area of London were recruited for voyages by both the EIC and the Virginia Company, with some, like captains Robert Adams (fig. 6) and Christopher Newport, sailing to both Virginia and Asia. Adams made at least five voyages to Jamestown for the Virginia Company between 1609 and 1613, before sailing for the EIC from 1617 to 1620. Newport also made five voyages to Jamestown, beginning with the initial expedition of the Virginia Company in 1607 and ending in 1611. By the next year he had begun sailing for the EIC and made three voyages to the East before dying in Bantam in 1617.[16]

It has long been recognized that there was a nexus of individuals like Adams and Newport involved with the commercial activities of the Virginia Company and the EIC in the early seventeenth century.[17] The relationship between the two joint-stock companies is seen clearly from the outset in the personage of Sir Thomas Smythe, who was both the first governor of the EIC and the first treasurer of the Virginia Company. While Smythe did not take to sea, many mariners plied the seas as employees of one company and/or the other, and supplemented their incomes by acquiring uncommon portable goods for private trade. It is therefore not surprising that archaeological research since 1994 on the site of James Fort, the initial Virginia Company settlement of its Jamestown colony established in 1607, has revealed the same sort of exotic wares reflecting global trade as those found in Limehouse. From contexts of the isolated military settlement consisting of tents, pit shelters, and mud-and-stud barracks, archaeologists have discovered objects like the Chinese porcelain dragon bowl that were not readily accessible to most English consumers and are unique finds in colonial English America.[18]

We know from documentary evidence that Chinese porcelain was of interest to Englishmen with ties to Jamestown from the outset of the settlement. One such gentleman is Sir Thomas Dale (fig. 7), who served as deputy governor of Virginia from 1611 to 1616 and in 1618 joined the EIC as commander of a fleet of ships dispatched to counter the aggressive behavior of the Dutch against EIC shipping and factories. Despite surviving shipwreck, near drowning, and sea battles with the Dutch, he was able to send his brother-in-law in England a box containing 82 pieces of porcelain while in Batavia, located fifty miles east of Bantam.[19]

There is also porcelain associated with the aforementioned Captain Christopher Newport through his son, also named Christopher. Any portable goods such as porcelain that were in the father’s possession at his time of death were not mentioned because Captain Newport wrote his will before departing on his third and last voyage for the EIC to Bantam in 1616. His will mentions property he bequeathed to his wife, and money and shares in the Virginia Company to be left to other family members.[20] Son Christopher, however, had been serving his father on the voyage as master’s mate, and made his will in 1618 while at sea and after his father’s death.[21] The son bequeathed many items that he stored in his cabin, such as clothing, books, navigational instruments, bedding, and even a Cheshire cheese. Of special note are several gifts of porcelain. To his mother he gave “three small Chyna paynted dishes” as well as one “Japan dish.” To “Doctor Meddows a preacher of good worde at Fenchurch” he left “sixe Chyna dishes paynted.” Christopher also mentioned “Chyna boxes,” which he assigned to his mother, his sister, and four women, but it is not known whether they were ceramic boxes. Contemporary Chinese porcelain forms known as pen boxes certainly existed, but there is also a 1621 reference to a “China Boxe” in Virginia that was definitely constructed of organic material. In that instance, English colonists visiting Indians on the Potomac River saw a “China Boxe at one of the Kings Houses.” The box was described as “made of braided Palmito, painted without, and lined in the inside with blue TaVata after the China or East India fashion.”[22]

Degrees of Separation

This short note was prompted by the wonderful, almost unbelievable, antipodal discovery of “twin” Chinese porcelain bowls—one in an exotic entrepôt of East Asia, and the other in the small, isolated English fort in Jamestown, Virginia—and just scratches the surface of understanding the global network of people and goods in the early seventeenth century. Whether they were adventurers, mariners, merchants, or privateers, the men who settled England’s first successful transatlantic colony at Jamestown had access to the same kind of goods as a Persian shah, Ottoman sultan, or a Swedish king.[23] As the archaeology of James Fort (est. 1607) has shown, at a time when Chinese porcelain was reaching England in only small quantities, it was considered important enough to acquire as a signifier of status by those who could.[24] In the words of Richard Hackluyt (the younger), Chinese porcelain is “the best stuV of that kind in the whole world.”[25] This is the opinion of someone who was a big promoter in the late sixteenth century of English settlement in North America, a signatory to the Virginia Company’s original charter, and an adviser to the East India Company. Degrees of separation.

Bly Straube, “Jamestown, Virginia: Virginia Company Period,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter and Angelika R. Kuettner (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2017), pp. 198–99.

I had mentioned in my 2017 article that evidence for two of the vessels was found at Jamestown. One was only minimally represented and included a rim fragment that, unlike the more complete vessel, has a straight profile like the bowl from Java. At the time I had considered that this was a saucer, but now it must be considered a second bowl. I am grateful to Merry Abbitt Outlaw, curator for the Jamestown Rediscovery Foundation, for this opinion.

Teresa Canepa, Zhangzhou Export Ceramics: The So-called Swatow Wares (London: Jorge Welsh Books, 2006), pp. 29–30.

I am grateful to ceramics scholar Teresa Canepa and Chinese archaeologist Li Jia’an for this information, personal communication 2010.

Scarlett Jang, “Realm of the Immortals: Paintings Decorating the Jade Hall of the Northern Song,” Ars Orientalis 22 (1922): 82.

William Foster, ed., The Journal of John Jourdain, 1608–1617, Describing His Experiences in Arabia, India, and the Malay Archipelago (Nendeln, Liechtenstein: Kraus Reprint, 1991), p. 316.

Ernest M. Satow, ed., The Voyage of Captain John Saris to Japan 1613 (London, 1697), p. 216, cited in Teresa Canepa, “The Portuguese, Spanish and Dutch Trade in Zhangzhou Porcelain (Part III),” Fujian Wenbo 78 (May 2012): 13.

Teresa Canepa, “Silk, Porcelain, and Lacquer: China and Japan and Their Trade with Western Europe and the New World, 1500–1644,” Ph.D. diss., University of Leiden, p. 213.

Anthony Farrington, Trading Places: The East India Company and Asia, 1600–1834 (London: British Library, 2002), pp. 77, 87.

William Foster, The Voyage of Sir Henry Middleton to the Molucca 1604–1606 (Millwood, N.Y.: Kraus Reprint, 1990), pp. 183–84.

Richard J. Blakemore, “Adventurers by Sea: The Trading Activities of Early Modern Sailors,” in Maria Fusaro, Richard J. Blakemore, Benedetta Crivelli, Kate J. Ekama, Tijl Vanneste, Jan Lucassen and Matthias van Rossum, Yoshihiko Okabe, Per Hallén, and Patrick M. Kane, “Entrepreneurs at Sea: Trading Practices, Legal Opportunities, and Early Modern Globalization,” International Journal of Maritime History 28, no. 4 (2016): 777–78.

Douglas Killock and Frank Meddens, “Pottery as Plunder: A 17th-Century Maritime Site in Limehouse, London,” Post-Medieval Archaeology 39, no. 1 (2005): 1–91.

William Strachey, A True Reportory of the Wreck and Redemption of Sir Thomas Gates, Knight, upon and from the Islands of the Bermudas: His Government of the Lord La Warr, July 15, 1610, reprinted in A Voyage to Virginia in 1609, edited by L. B. Wright (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 2013), p. 72.

Philip L. Barbour, The Complete Works of Captain John Smith (1580–1631), 3 vols. (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press for the Institute of Early American History and Culture, Williamsburg, Va., 1986), 1:240.

Strachey, A True Reportory, p. 72.

Alexander Brown, The Genesis of the United States, 2 vols. (Boston: Houghton, MiZin, 1890), 2:812, 2:957–58.

Boies Penrose, “Some Jacobean Links between America and the Orient,” Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 48, no. 4 (October 1940): 289–303, and Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 49, no. 1 (January 1941): 51–61.

Straube, “Jamestown, Virginia: Virginia Company Period,” pp. 186–204; Beverly Straube, “European Ceramics in the New World,” Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New Hampshire for the Chipstone Foundation, 2001), pp. 47–71; William M. Kelso and Beverly Straube, “2000–2006 Interim Report on the APVA Excavations at Jamestown, Virginia,” Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities, 2008; William M. Kelso, Beverly Straube, and Daniel Schmidt, “2007–2010 Interim Report on the Preservation Virginia Excavations at Jamestown, Virginia,” Preservation Virginia and the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 2012.

Foster, Voyage of Sir Henry Middleton, pp. lxviii–lxxi; Canepa, “Silk, Porcelain, and Lacquer,” p. 215.

Prob 11/132/424 (V 208–209), The National Archives, Washington, D.C.

Prob 11/132/280 (V 149–150), The National Archives, Washington, D.C. I am grateful to Martha McCartney for transcribing this document.

Samuel Purchas, Hakluytus Posthumus, or Purchas His Pilgrims, 20 vols. ([1625]; Glasgow 1905–7), 19:151–52.

Ronald W. Fuchs II, “One of the Earliest Pieces of Chinese Porcelain in Virginia,” Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New Hampshire for the Chipstone Foundation, 2019), pp. 49–57; Straube, “European Ceramics,” p. 52.

Merry Abbitt Outlaw, curator for the Jamestown Rediscovery Foundation, is currently researching for publication the porcelain recovered from the Jamestown Rediscovery archaeological excavations.

Richard Hakluyt, The Principal Navigations, Voyages, Traffiques, & Discoveries of the English Nation, 12 vols. (Glasgow: James MacLehose & Sons, 1904), 6[1589–1600]:356.Figure 1 Bowl, Jingdezhen, China, ca. 1572–1620. Slip-decorated porcelain. D. of footring 2". (Courtesy, Jamestown Rediscovery Foundation; photo, Robert Hunter.) This fragmentary example was recovered from disturbed archaeological deposits at James Fort.